Ten-year-old Naima lives in a rural Bangladeshi village with her mother, father, and younger sister. Being the older sister means she has more chores, more household responsibilities, and less time to play with her friend Saleem. Moreover, he's a boy—and at her age, it's not considered seemly to play with boys anymore. It's not much consolation that she's the best painter of alpanas--traditional patterns drawn in rice-powder paint—in her village.

What good are alpanas? Naima wonders. They don’t earn her any money to help her family pay for her father's new rickshaw, or to help her sister to go to school. Her father says a daughter is as good as a son, but she isn't allowed to work to help her family. So Naima hatches a plan: if a daughter is as good as a son, then surely she, like Saleem, could help her father by earning fares driving his rickshaw. One afternoon she decides to try her idea while her father is resting. But disaster ensues. She loses control of the rickshaw and it crashes into some bushes.

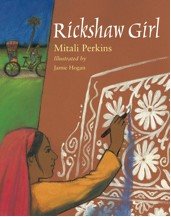

How can she make everything right again, and help her father earn the money to fix the rickshaw, when her only real talent is painting alpanas? I don't want to give away the ending to Mitali Perkins' charming middle-grade book Rickshaw Girl (upcoming Feb 2007), but the secret lies in the modernization of Bangladeshi society, more prominent roles for women in village life, and the idea of microfinance providing small loans to village residents. And the end is truly heartwarming and uplifting—I was cheering for Naima's pluck, her friend Saleem's loyalty, and, especially, her father's support of his daughter in a traditional society where the idea of women working outside the home is often greeted with suspicion.

Less and less often is this the case, fortunately. It reminded me of the fact that my own father, born in Pakistan, could have been equally traditional about the role of women. But, like Naima, I've been lucky to have a father who never made me feel as though there was anything I couldn't accomplish simply because I was female. I hope the idea of microfinance and microcredit spreads throughout the world to other needy societies, and that women around the world begin to experience the same kind of blossoming opportunities. Perkins' book will go a long way towards informing young readers—and their parents—of these possibilities.

I also want to add a quick word about the illustrations by Jamie Hogan, which are deceptively simple and sketch-like but are just as charming as the story, incorporating some traditional alpana designs. This would be a great addition to any collection of multicultural books.

No comments:

Post a Comment